Parents’ Guide

to Children’s Vaccines

Sections

Acknowledgments

This guide, much like Boost Oregon itself, is the result of a community-wide effort. Joel Amundson, M.D., and Nadine Gartner are the primary authors. Gary Ashwal, Paul Cieslak, M.D., Alison Dent, Stacy Matthews, Michele Rossolo, and David Solondz, M.D., provided invaluable input. Many thanks to the parent volunteers who contributed their personal stories to this guide.

Diana Tung designed the guide and created original graphics for it. Bob Land proofread the guide. Generous grants from the Juan Young Trust, Oregon Immunization Program, and Spirit Mountain Community Foundation made these guides a reality.

Finally, we are grateful for the hundreds of individual donors—parents, community members, and medical professionals—who donated money toward this effort. Boost Oregon does not accept donations of any kind from pharmaceutical companies.

Copyright © 2017 Boost Oregon. All rights reserved. Boost Oregon® is a registered trademark of Boost Oregon.

You can order printable and physical copies of our Parents' Guide to Children's Vaccines through our store.

Introduction

Boost Oregon knows that you want to make the best decisions for your child’s health. But, like most subjects related to parenting, there is a lot of seemingly contradictory information out there about children’s vaccinations.

This guide helps you sort through the noise and understand the evidence-based facts about immunization. You have probably researched online and spoken to your friends and family about the benefits and perceived risks of various vaccinations. Now is your chance to learn from medical experts and parents like you who had questions and concerns about their children’s vaccinations.

In addition to this guide, the rest of Boost Oregon’s website offers information and resources that will aid you and your child on your journey to good health. Get answers to your vaccination concerns, learn other parents’ stories, and connect with a community that cares about the health and well-being of our children.

Boost Oregon also hosts community workshops for parents seeking answers to their vaccine-related questions. Check out events for future dates and locations.

Thank you for picking up this guide. We know that parenting can be challenging, and we are here to support you. As an organization led by parents like you, Boost Oregon aims to give every child the best shot at a healthy life.

A Note from Our Founder

Like you, I’m a parent who cares deeply about my children’s health. When I became pregnant with my first child, I learned that many parents around me—smart, educated, caring people—chose not to vaccinate or to delay their children’s vaccinations. I wondered if I, too, should make similar decisions for my children.

I did my own research online and was surprised by the conflicting information that surfaced. I had a lot of questions. My husband and I chose a pediatrician whom we trusted, and he helped us sort through the information and answer our questions. We chose to vaccinate our child on schedule, and we made the same decision with our second child.

I created Boost Oregon because I recognized a need for vaccination education in our state. I know that you, like me, want to make the best possible decisions for your child’s health. I hope that this guide, as well as our other resources, will enable you to do just that.

Nadine A. Gartner

Founder, Boost Oregon

What Are Vaccines, and How Do They Work?

The goal of vaccines is to greatly reduce the complications caused by childhood diseases. Although some diseases might be good for us to catch and leave us stronger, others cause more harm than good and leave us weaker. Vaccines prepare our bodies to fight against harmful diseases that we are likely to encounter in the world.

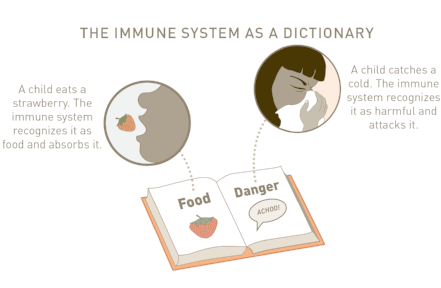

To understand how vaccines work, imagine that your immune system is a dictionary. For every substance that your body encounters, the immune system records a definition and an action. The definition is the description of the substance. The action tells the body what to do with the substance, like absorb it or attack it.

But, before your body knows what to do with something, it must identify the substance first. The way your body identifies something is based on the shapes found on the surface of that thing. These shapes are called antigens—physical characteristics of an object that the immune system can recognize. Vaccines help your body identify what infections look like so that the immune system can use its natural defenses to treat them.

For example, imagine a child eating a strawberry. It is important that the immune system has identified the strawberry as food and absorbs it. Now imagine a child who catches a cold. It is important that the immune system has identified the cold as harmful and attacks it. Vaccines don’t change how your body acts when it encounters something; they just help your body identify what it encountered.

Children are born with a bunch of blank definitions for serious childhood diseases like measles, pertussis (whooping cough), rotavirus, and others. If the child is unvaccinated and encounters one of those diseases, it takes time for the child’s immune system to examine the disease, record a description of it, and decide if the disease should be attacked. Unfortunately, this process takes so long that, by the time the definition and action are recorded, the disease may have already caused some permanent harm to the child. Vaccines teach our immune systems to fight diseases that otherwise would take them too long to recognize as harmful.

A vaccine for a particular disease may contain deactivated bacteria from that disease, or a deactivated or weakened live virus. The vaccine is given to a child with blank definitions. The child’s immune system can take its time defining what the disease looks like and noting to attack it. When encountering the live disease for the first time, the child’s immune system will be ready to fight it immediately and prevent serious illness or permanent harm.

Are Vaccines Still Necessary?

Although we may not see many vaccine-preventable diseases in Oregon or elsewhere in the United States, it does not mean that these diseases have been eradicated. Vaccines have worked so successfully that we have seen a decrease of the diseases in the United States.

However, when vaccination rates decrease, diseases become more common in our communities again. For instance, the measles outbreaks across the United States in 2014 and 2015 occurred largely in unvaccinated persons.

Imagine a community garden filled with healthy vegetables and beautiful flowers. In addition to watering the plants and mulching the soil, the volunteers must weed regularly. If too many volunteers show up and remove all of the weeds, they may decide that the number of weeds has dropped so much that no more volunteers are necessary. Without regular weeding, the weeds grow uncontrollably and threaten the vegetables and flowers. The garden then needs to bring back its weeding volunteers.

By going back and forth with either too many or too few volunteers, the garden gets caught in a never-ending cycle. The better alternative would be to determine the right number of volunteers needed to keep the weeds at a level acceptable to the community garden. Vaccines work much in the same way.

If we stop vaccinating because we don’t see a particular disease in our community, that disease will return. Some diseases, like smallpox, may be eradicated globally and allow us to stop vaccinating for it. But reaching the point of eradication takes decades, and that process takes even longer the more we stop and start vaccinating. We have a long way to go to eradicate many other childhood diseases, but the more consistent effort we invest, the more progress we make.

Leah, Portland OR

"I have lived and worked in other countries, and I have family in northeastern Brazil, a place where some vaccines only became available to the general public recently. I have family and friends who are doctors and scientists, some of whom have treated illnesses that could have been prevented with vaccines.

They have had to comfort the parents of children who were disfigured, brain- damaged, or died as a result of preventable illnesses. I lived in Denver, Colorado, where one of my colleagues still walks with great difficulty and the help of crutches, as he has for most of his life, because he did not receive the polio vaccine as a child and then contracted the disease.

I know that most people in Oregon have not seen the horror that diseases can do. That is not just because we are lucky. That is because modern medicine has developed vaccines to prevent the spread and the damage of those diseases. Recently while on a vacation, my family witnessed a terrible car accident. One car had flipped over several times and landed on its roof. In the other car, a passenger was stuck between his steering wheel and his seat back. As the first responders, we kept the victims alert and talking until the paramedics arrived. Every single one of them was wearing a seat belt. Every single one of them walked away with only minor injuries.

Their outcome was not luck; it was the result of the science behind seat belts, air bags, and crumple zones, technology that allows us to live longer, healthier lives and to survive the things that killed and maimed people in the past.

Similarly, I think of vaccines as life-saving technology. My children and myself

will be out in the world, and there is always a chance that we will be exposed to a disease that could hurt or kill us. But, thanks to the modern technology of vaccines, we have a chance to walk away from them, unharmed."

Are Vaccines Safe?

Vaccines are some of the most tested and closely monitored medicines we take. Thousands of hours of research from around the world go into each vaccine to ensure they are safe and effective before they are distributed to the public. Even after they are released for use, vaccines are tested continually and monitored for safety.

For vaccines to be worthwhile, it is important that they have fewer side effects than the harm that diseases themselves would cause. There are many ways that vaccines can be formulated to make sure they are safe and effective. Some vaccines may contain a much smaller dose of the bacteria or virus than would be present in the disease itself. Live virus vaccines can be cultured in environments that promote milder strains, making a case of measles feel more like a common cold. Other vaccines may omit the specific antigens in a disease that are known to cause bad reactions.

When we share a disease’s definition with our immune system through vaccination, we have an opportunity to pick and choose the antigens that will produce safe and effective immunity and leave out problematic antigens that may cause more harm than good. For example, imagine that we wanted to create a vaccine for strep throat.

Let’s say that your body identifies the strep bacteria by these marks

Now, imagine that some of your own cells have these marks on their surface

Note that two of these marks look the same. The strep bacteria and your own cells share a similar shape.

As a result, sometimes children develop autoimmune disease after strep throat infections. So, if we were to make a vaccine for strep throat, one way to make that vaccine safer than catching strep throat would be to omit that shape. The remaining shapes would be enough for your body to identify it as strep bacteria but would reduce the risk that your body attacks itself.

The vaccine would look like this

The vaccine includes all the shapes of strep bacteria without the shape that is found on your cells.

This was the process used in the current diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccine and is one of the reasons that babies tolerate the vaccine much better than the effects from actually catching pertussis. By reducing the intensity of a reaction that a disease would cause, a vaccine is far less likely to trigger an unwanted reaction than the disease itself. Vaccines enable your immune system to more accurately and safely distinguish between what is disease and what is your body.

Shona, Ashland, OR

"When my daughter was about 1 year old, there was a lot of discussion in the media about the safety and potential side effects of vaccines. I became concerned and decided to learn more about the pros and cons of vaccines.

In reviewing reputable resources and discussing my concerns with my pediatrician, I found the advantages far outweighed any potential side effects, and the question then became, how could I not vaccinate my child? As any

reasonable parent would, we want to protect our children.

Vaccines are the best preventable care we have to protect against disease, and I fully welcome and endorse all vaccines now."

What Is Community Immunity?

Community immunity, also known as “herd immunity,” is when the majority of a community is vaccinated and able to protect those who are unvaccinated. When most people are immunized, diseases can’t spread as easily. This protects the few among us who are not immune.

It is important that those of us who can receive vaccines do so in order to protect those who cannot. Among the unvaccinated are people whom we know and love: babies, who are too young to be immunized; people with weak immune systems due to disease or medical treatments, like chemotherapy; pregnant women; senior citizens; and anyone allergic to a vaccine.

For diseases like measles and pertussis, about 90% to 95% of people in your community must be vaccinated to shield the people most at risk. For some diseases, like polio, an 80% to 85% vaccinated rate may be enough. Oregon’s vaccination rates for certain diseases fall short of those thresholds, and some schools have as many as 40% to 80% of children missing vaccines. Your child or community could be at risk. Vaccinating your child and yourself is a wonderful way to benefit your family’s health, as well as the health of your friends and neighbors.

Kellei, Talent, OR

“My son, Pete, was diagnosed with a pineoblastoma (a very rare and aggressive brain tumor) just before his second birthday in 2005.

This diagnosis gave him only a 5% chance of survival. He underwent several surgeries to remove his tumor. Then we began treatment that lasted a year and included several different types of chemotherapy drugs and radiation. Of course, these poisons administered to Pete were to kill his cancer, but they also took a toll on his little body. There were many times his blood counts were so low that his immune system wasn’t able to protect him at all.

During these times, it was super scary because he was extremely susceptible to catching any type of illness. If we went out, Pete had to wear a mask to try and put a barrier between him and the outside world. People would look at him and step away like they thought they would catch something from him.

Yes, Pete had received his appropriate vaccinations.

But I don’t think people understand that when they choose not to vaccinate their children, they are not only affecting their own families, they are also putting others (like Pete) at risk.

While Pete was on treatment, we knew several families who lost their children, not because of their cancer, but because of illnesses they caught while their immune systems were compromised from their treatment.

Pete is now 10 years old, healthy, cancer free, and his immune system is protecting him again. But there are countless other children just beginning the fight for their lives. Herd immunity is the only way to protect these kids."

So, Why All the Fuss?

If vaccines are safe and necessary, then why all the fuss to the contrary? Opposition to vaccination has existed as long as vaccination itself. In the 1800s, a small but vocal minority opposed the smallpox vaccine. Today, there is similar opposition to the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) immunization; the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine; and the use of a mercury-containing preservative called thimerosal.

It’s confusing to sort through the sea of vaccination information that exists online and within our communities. You can and should raise questions with your child’s medical provider, who is experienced in children’s health and likely has spent years understanding and administering vaccines. Boost Oregon, an organization led by parents like you, can assist you through its community workshops and other resources.

How to Sort through the Noise

(Adapted from “Tips for Evaluating Immunization Information on the Internet,” Multnomah County Health Department.)

As you do your own research about vaccines, keep a few things in mind:

The information provided should be based on sound scientific study. If it is, it will usually be endorsed by groups or institutions dedicated to science, such as professional associations or universities.

Transparency. A good health website should show who is responsible for the site and a way to contact the webmaster.

Look at some other articles on the website and see if they have an agenda. If most or all of the articles are one-sided, such as a website that exclusively attacks conventional medicine without ever defending it, there’s a good chance it’s not telling the whole story.

Beware of suggestions of “conspiracies.” There is a robust network of honest scientists who monitor vaccine studies without financial ties to industry. And, as explained later in this guide (see “Aren’t Vaccines Just Moneymakers for Pharmaceutical Companies?”), vaccines create such little profit that maintaining a vast global conspiracy would cost way more money than what pharmaceutical companies could make from it.

Media attention does not necessarily mean a claim is true. You may see a celebrity advocate for or against something, but it’s important to dig beneath the media attention and see what experts in the field say.

When evaluating a particular claim or study, know that an honest perspective is a balanced one. Legitimate studies will not cherry-pick their results or leave out relevant factors or variables. And, when in doubt, you can turn to your trusty search engine and type: “Debunk _____” (insert whatever claim you’re reviewing). Chances are that, if a particular claim does not hold up, others have already done the work for you and demonstrated its inaccuracy.

Can Vaccines Cause Harm?

Vaccines, like all medical interventions, can cause harm. The important thing is that vaccines cause less harm than the diseases against which they provide protection.

Although very rare, certain vaccines may cause an allergic reaction in some people. If you or your child has a known allergy, talk to your medical provider about your concern. Some vaccines, like the original rotavirus vaccine or a vaccine for H1N1 flu in the 1970s, caused more harm than good by making people almost as ill as the diseases themselves. Those vaccines were pulled off the market and replaced with better, safer vaccines that protected patients from the harmful effects of the original diseases.

It’s important to note that no vaccine recommended for use has been found more harmful than the disease. Over the several decades in which vaccines have been readily available to us, only a few vaccines have been recalled because they were found to cause almost as much harm as the disease itself.

In comparison, consider medications for treatment of a disease. Medicines intentionally alter your body’s function and sometimes have vastly different effects than intended. Vaccines, on the other hand, work with your body and train your immune system to fight against harmful diseases. So, what about reports that vaccinated people still get sick? To understand the numbers, you have to look at the total population and not just the outbreak.

Imagine an outbreak in a school where seven children get sick, five of whom were vaccinated. You might think that the vaccine isn’t helping anyone or that it even makes things worse. But you must consider the total population of the school: 50 children in total, 46 of whom are vaccinated and four are not. Of the 46 vaccinated children, five of them got sick, which is only 10% of all the vaccinated children. Among the unvaccinated children, two of them got sick, which is 50% of the unvaccinated children. It only appears that the vaccinated children have more illness because more children are vaccinated.

If 50 children were vaccinated and 50 children were not, there would be five vaccinated children getting sick (10%) and 25 unvaccinated children getting sick (50%). So, it is important to compare equal population sizes to get the full picture.

Alison, Portland, OR

"Terror is the word I use to describe what it feels like to learn that your child has cancer. A chill that takes over your body, rapid heartbeat, mind racing.

But we cheered in our 6-year-old daughter’s hospital room when told that her type of leukemia has a treatment plan with a high cure rate. It would mean more than two years of bone marrow biopsies, surgeries, transfusions, spinal taps, and chemotherapy. So much chemo. The drugs would kill the cancer and save her life, but they would also kill her immune system, leaving her vulnerable. We did what we could to keep her safe as she endured the treatment—stocking up on hand sanitizer and limiting where we took her. Weeks were spent trapped in a hospital isolation room when fevers struck.

We did our best to push aside the terror and keep our family thriving, but I could not stop the terror when told that there was a child with whooping cough at my daughters’ school. Nor could I stop it as we canceled our trip to Disneyland during the measles outbreak.

Our community was not protecting our daughter.

Our loving community that cooked us meals, helped care for our other daughter, sent our children gifts; the wider community that made a custom wig, built a dream playhouse, and provided a special getaway. I will never forget the waived dental bill, or the unordered donuts that appeared with a hot chocolate. There are so many kind people who wanted to help.

I long for a day when all forms of cancer have a treatment plan. I hope that the treatments we do have can become less toxic. In the meantime, I want everyone to know that they can help.

Vaccinating your children and keeping your community healthy are the most important things you can do to help all people with cancer."

Aluminum is the most common metal found in nature. In the first six months of life, your baby receives about 4 mgs of aluminum if getting all of the recommended vaccines, compared with 120 mgs if your baby is fed soy-based infant formula.

What About the Aluminum in Vaccines?

Aluminum is a common and natural metal. Aluminum enhances the immune response to vaccines by allowing for lesser quantities of active ingredients and, in some cases, fewer doses. Here are the facts about aluminum:

Aluminum is the most common metal found in nature and is part of our daily environment. It exists in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat. That’s why it was chosen for vaccines: our bodies already know how to process it and do so on a regular basis.

The amount of aluminum contained in vaccines is small. In the first six months of life, your baby receives about 4 milligrams of aluminum in getting all of the recommended vaccines. However, during the same period, your baby will ingest about 10 milligrams of aluminum if you breastfeed, 40 milligrams if you feed regular infant formula, and up to 120 milligrams if you feed soy-based infant formula.

Typically, your baby has between one and five nanograms (billionths of a gram) of aluminum in each milliliter of blood. Researchers have shown that, after vaccines are injected, the quantity of aluminum detectable in an infant’s blood does not change and that about half of the aluminum from vaccines is eliminated from the body within one day.

(Data from Vaccine Education Center, “Vaccine Ingredients: What You Should Know,”)

Do Vaccines Contain Mercury?

Thimerosal, a mercury-containing compound, was a common preservative used in vaccines in the 20th century. By the late 1990s, however, thimerosal was removed from children’s vaccines to ease parents’ concerns.

Now, children’s vaccines come in single-dose vials that don’t need preservatives. Since 2001, vaccines recommended by the CDC for children under 6 years of age are thimerosal-free, except in multidose vials. Most single-dose vials and prefilled syringes of flu shots and the nasal spray flu vaccine do not contain thimerosal or any other preservative.

SABRINA, ASHLAND OR

"I lost my son to bacterial meningitis one day shy of his second birthday. I would give anything for him to have had the vaccine that is currently available.

No child should die from an illness that is preventable."

Can I Space Out My Child’s Shots?

Many people assume that the current vaccine schedule was not created for the benefit of the baby but for the preference or convenience of the medical industry—and, if so, that there could be an alternative vaccine schedule that is actually better for the baby.

But that is not the case. The current U.S. vaccine schedule is the product of thoughtful and informed collaboration among specialists in pediatrics, infectious disease, and public health, specifically and only for the benefit of the child. It is based on when the vaccines are best tolerated and safest, and offer the greatest protection to the child.

Let’s review what went into the recommended schedule so that you can see the logic behind it.

Do Maternal Antibodies Protect My Baby?

Mothers pass protective antibodies across the placenta to their babies in the weeks before birth. These antibodies stay in the baby for about six months, and they offer helpful protection for the baby. However, they also have limitations. The antibodies that are given to the baby form “passive immunity,” meaning that those antibodies cannot be remade. When the baby makes her own antibodies, that is called “active immunity,” and it is more effective in fighting off disease. That is why vaccines still offer significant protection during this period.

Are There Varying Risks of Infection at Different Ages?

Some infections are much more severe the younger the infant is, such as pertussis, haemophilus, and pneumococcus infections. So, the most important time to protect the baby against them is early in infancy, and the longer a vaccine for these diseases is delayed, the less benefit an infant will receive from the vaccine.

With boosters at 2, 4, and 6 months, the baby’s active immunity builds up during this critical period as antibodies from the mother fade away, giving the baby a smooth transition to self-protection by the time they are gone. If, instead, vaccines did not start until 6 months of age, the baby’s active immunity would not be fully developed until months later. That would leave the baby with the least protection during the most critical period.

When Do Vaccines Produce the Best Immune Response?

There is a big difference between when vaccines produce the strongest immune response versus when they offer the greatest benefit. In many cases, the immune response to a vaccine increases the older a child is. But it isn’t the strength of an immune response that matters most to the child’s health; it’s to what degree children do or don’t suffer any lasting health effects when all is said and done.

A perfectly adequate, modest immunity throughout infancy is far more desirable than suffering through the highest risk period with no immunity just so they can experience a stronger immune response to that vaccine at a later time—when there may be less or no risk from the disease anyway. Furthermore, a stronger immune response to a vaccine sometimes means stronger side effects.

For some vaccines, like measles, young babies do not respond well, so the vaccines are recommended only after 12 months of age. For other vaccines, such as pneumococcal vaccine, babies can respond well as early as 2 months of age (and babies that young are known to be at high risk), so vaccination is recommended to begin at that age.

The ideal situation you want to achieve is just enough immunity to stop a disease from doing harm, at the age when that disease causes the most harm. This can differ greatly depending on the vaccine, which is why different vaccines are at different places on the childhood schedule, all very precisely placed and timed to get

the best benefit with the fewest side effects. Because of this, altering the schedule will generally result in more side effects, less benefit, or both—you would be giving them at a time other than the time when their benefit-to-risk ratio is at its best.

Should My Baby Get Multiple Vaccines at One Time or Single Shots at Multiple Visits?

Once leaving the mother’s womb, which is a sterile environment, your child faces trillions of cells of bacteria, viruses, and yeast through the skin, nose, throat, intestines, and so on. Your baby keeps these organisms from causing serious disease by making immune responses to all the different cells—all at the same time. A child can respond to all of them simultaneously because of the billions of immunologic cells circulating through the body, each capable of doing its own work.

The 14 vaccines found on the childhood schedule contain a total of about 150 immunologic components—a tiny number on the immunologic scale. Out in the world, each bacterium alone can contain 2,000 to 6,000 immunological components, and your child processes many of them simultaneously. The entire vaccine schedule even all at once would be smaller than what your baby’s immune system manages every day.

Other considerations include the hassle for your family and the trauma for your child. It’s easy for doctors’ offices to do your shots on different days. But it’s most difficult on your family and your child. It means doubling the number of times your baby needs to get needle pokes. It also means scheduling more frequent doctor appointments and missing more time from work or school. And taking more time to complete a vaccination series obviously delays the protection that the vaccines offer. Perhaps these downsides would be worthwhile if we had evidence that giving vaccines on a more drawn-out schedule was better for babies. But we know that it isn’t.

Rachel, Portland, OR

"For our first child, we gave him most (not all) of the recommended vaccinations, on a delayed schedule, one at a time. As he grew older and he was more afraid of shots, it became a huge challenge and inconvenience to go back and forth to the doctor.

Due to my exhaustion of schlepping kids to the doctors on multiple occasions, my son’s emotional fear of needles as he grew, and the fact that I had yet to read any current medical evidence that routine vaccine schedules were dangerous (in fact, I started hearing about local outbreaks of preventable diseases in our hometown of Portland, OR), we decided to follow the CDC guidelines for our daughter.

I have cut my doctor trips by more than half, and I also have peace of mind when I let her play and interact with children from all geographic locations both at home and when we travel."

The global total of all vaccines—for adults and children by all pharmaceutical companies that produce vaccines—represents only 5% of a trillion-dollar, worldwide pharmaceutical industry.

Are Vaccines Just Moneymakers for Pharmaceutical Companies?

Some people decline vaccines because they do not want pharmaceutical companies to profit. Companies do make money on vaccines, and they have acted greedily and dishonestly at times (e.g. price-fixing for insulin or denying the addictive nature of opioids). But pharmaceutical companies make far more money selling treatments for diseases than selling vaccines.

Currently, healthcare in the United States is a for-profit system. Hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies require payment for goods and services. Pharmaceutical companies make money by selling their products, including vaccines. They also make money from chemotherapy treatments and coronary bypass surgery, but patients do not refuse treatment for cancer or heart disease solely for that reason. The same standard should apply to vaccines, which are life-saving medicines that prevent the need for costly treatments.

Treatment costs more than prevention. Compare the cost of one case of measles to the cost of the MMR vaccine. There are two categories of costs for measles infection: The cost of treating the disease (supportive care, hospitalization, and therapeutics), and the cost of preventing the spread of disease. Treating a single case of measles in the hospital averages $14,456. The cost of preventing its spread depends on the number of people possibly exposed, require post-exposure preventative treatments, and develop measles. The average cost of a public health response to one measles case is $181,679. Comparatively, the MMR vaccine series only costs $165 ($82.50/dose) and provides protection for life. So, from a financial perspective, it is much more profitable for pharmaceutical companies to sell treatments for measles infection instead of vaccines for measles prevention.

Cost of MMR Vaccine vs. Measles Hospitalization

MMR vaccine series: $165

Measles hospitalization: $14,456

What about newer vaccines that may cost more or be distributed more widely? Let’s look at COVID-19 vaccines and treatment: In 2021, when the vaccines became widely available in the United States, the costs were $19.50 per dose of Pfizer, $25-$37 per dose of Moderna, and $10 per dose of Johnson & Johnson. While the majority of people infected by COVID-19 manage their symptoms at home, a doctor may recommend monoclonal antibody therapy, which ranges from $310-$750 per dose. If a person needs to go to the hospital, the costs increase exponentially. On average, the total cost of hospitalization for COVID-19 infection is about $73,300. Treatment may range from supplemental oxygen to full mechanical ventilation with sedation, which require drugs produced by pharmaceutical companies. Remdesivir, an antiviral therapy authorized for emergency use, costs $3,120 for a 5-day course. If the patient’s condition worsens, another drug called tocilizumab may be prescribed; it costs $2,416.76 per standard dose. In short, it may cost thousands of dollars to treat a person with COVID-19 infection, most of which benefits the pharmaceutical companies, but it only costs $10-74 to fully immunize that person.

Vaccines represent only about 5% of the trillion-dollar, global pharmaceutical industry. The global total sales of all vaccines—for adults and children by all pharmaceutical companies that produce vaccines—was $59.2 billion in 2020. Total global pharmaceutical sales in that year were $1.07 trillion. Pharmaceutical companies profit from selling vaccines, but those profits are a tiny portion of their overall sales.

Declining vaccines because you do not want pharmaceutical companies to profit from you or your child puts you and your family at risk for serious diseases that require costly treatments. If you get sick, it only benefits the companies more in the long run.

How Do Vaccines Fit into a Natural Lifestyle?

Perhaps you value following a natural lifestyle and intend to raise your child that way. That may mean, among other things, extended breastfeeding, cloth diapering, growing and eating organic food, and using environmentally friendly house-cleaning products. Some parents think that vaccines, which are produced in laboratories and administered in doctors’ offices and health clinics, are unnatural, and that it is better for their child to catch the disease and create immunity that way.

But catching preventable diseases can have dire consequences. The Great Flu Pandemic in 1918, for instance, infected 500 million people globally and killed 3% to 5% of the world’s total population.(Tauenberger, J. K., Morens, D. M. “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics.” Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006; 12(1):15–22)

The Ebola outbreak in 2013–2015, which primarily affected West Africa, infected nearly 29,000 people and caused over 11,000 deaths. Closer to home, the measles outbreak in the United States in 2015 infected 159 people across 18 states and Washington, DC.

Before the measles vaccine, nearly every American became infected and hundreds died from it each year.

Because we live in a time and place with access to good medical care and treatments, it is unlikely that your child will die from measles or any other vaccine- preventable diseases.

However, getting sick and requiring treatment negatively affect your entire family’s quality of life. You and your child will be forced to miss several days or even weeks of work and school as your child receives treatment and is isolated to keep from infecting other children. Your child may suffer long-term effects from the treatment or disease, like an increased resistance to antibiotics, scarring on the skin from chicken pox or measles, shortness of breath from whooping cough (pertussis), sterility from mumps, liver damage from hepatitis B, or kidney problems from pneumococcal disease.

Vaccines actually benefit natural health in the following ways:

Discourage formation of superbugs. Because vaccines introduce the immune system to a small part of the disease, which then triggers your body to build up its own immunity to the disease, vaccines discourage formation of super bugs. Treatment for a disease, on the other hand, selects for resistance and strong infections: When a virus or bacterium is defeated initially by antibiotics or antivirals, a small amount of virus or bacteria may still linger without causing disease. Those few remaining bugs tend to be more resilient. As they remultiply in the future, they are increasingly resistant to prior treatment and become superbugs. Vaccines, on the other hand, prompt the body to use its own immunity to defeat the virus or bacterium and prevent the development of superbugs.

Teach our bodies to fight illnesses naturally. Vaccination gives the human body the tools to build up its own immunity against a particular disease. If, after vaccination, our bodies encounter a particular disease in the world, they will know how to fight it because our immune system has already filled in the definition for that disease (see “What Are Vaccines, and How Do They Work?”).

Reduce total pharmaceutical usage. Vaccines contain very few immunological components and ingredients, especially compared to antibiotics. If, instead of vaccination, your child contracts a disease, the treatment received could include antibiotics, antivirals, and perhaps other drugs with far more ingredients and components. These treatments can have significant side effects, from stomach upset with diarrhea and yeast infections to rashes and liver and kidney complications.

Reduce environmental pollution. If your child requires hospitalization or any outpatient procedures to treat a vaccine-preventable disease, you will be increasing the amount of environmental waste. From disposable gloves and IV bags to single-use surgical devices and frequent bedsheet changes, the amount of garbage, water, and electricity required to sustain a single patient’s treatment is astonishing. If your child is vaccinated, all of that waste is avoided.

Can Vaccines Cause Autism?

As a parent, you may be concerned about the increasing prevalence of autism and no known cause for the condition. Over 100 different studies have looked for a possible connection between vaccines and autism, and none have found evidence of a link. For more information about potential causes of autism, check out the Autism Science Foundation.

The myth surrounding vaccines and autism has shifted over the years. In 1998, a British researcher, Andrew Wakefield, suggested that the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine might cause autism. To determine whether Wakefield’s hypothesis was correct, researchers performed a series of studies comparing hundreds of thousands of children who had received the MMR vaccine with hundreds of thousands who had never received the vaccine. They found that the risk of autism was the same in both groups and that the MMR vaccine did not cause autism.

In 2010, Wakefield’s study suggesting that the MMR vaccine might cause autism was fully retracted by its publisher. The study was found to be scientifically unsound because Wakefield had manipulated and falsified his data. Since then, Wakefield’s medical license has been revoked.

Once Wakefield’s theory was debunked, a new myth emerged, claiming that the ingredient thimerosal caused autism. Thimerosal is a mercury-containing preservative that was used in vaccines to prevent contamination. Due to public pressure, thimerosal was removed from children’s vaccines in 1999, and several studies since have shown no link between thimerosal and autism.

The latest myth claims that autism is caused by children receiving too many vaccines too soon and being exposed to too many immunological components. Several facts make this highly unlikely:

As discussed earlier (“Can I Space Out My Child’s Shots?”), although the number of vaccines has increased during the past century, the number of immunological components in vaccines has decreased.

The immunological challenge from vaccines is tiny compared to what babies encounter every day.

Children have an enormous capacity to respond to immunological challenges because humans have the capability to make between 1 billion and 100 billion different types of antibodies.

Given the number of immunological components contained in vaccines, a conservative estimate would be that babies have the capacity to respond to about 10,000 different vaccines at once.

Amy, Southern Oregon

"I breastfed both of my daughters for nearly two years each and vaccinated my children on a regular schedule until the year 2010, when my oldest daughter was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism. I had read articles in the media and heard from some of my friends who did not vaccinate their children that vaccinations could have caused this 'disorder' in my daughter.

Around the same time I was researching vaccinations, the actress Jenny McCarthy was widely promoting her book about her son, her choice not to vaccinate, and autism. I was convinced not to vaccinate my daughters anymore.

We were only about two weeks late with their next vaccination appointment when I reconnected with my friend Sabrina. She had lost her son, Dylan, to meningitis, a vaccine-preventable disease. I met with my doctor in Ashland, who was willing to have a long discussion with me about the importance of being fully immunized. Both of my daughters have continued to stay up to date with their vaccines to this day.

As a mother who has a daughter with autism, I don’t believe that there is enough concrete information to suggest that vaccines could have caused my daughter to have autism. When she was born, before any vaccinations, she would shake her tiny hands in front of her mouth. This was unusual compared to the other babies we were around. This has now evolved into the stemming that she does, which is an indicator for autism and autism spectrum disorders.

I urge everyone to vaccinate their children. I don’t ever want to have to say ” good-bye to my babies and forever regret not doing something that could have saved their lives."

How Can I Comfort My Child before and after Shots?

As parents, we have a tremendous amount of power when it comes to comforting our children. The same is true when a child receives vaccinations. To make the process as smooth as possible, try some or all of the suggestions below.

(Adapted from "Parents Can Help Reduce Pain And Anxiety From Vaccinations")

Before and during the shots:

Talk to your child on the morning of the shot and walk through the events of the day, including the medical visit and shot. Then talk about the next event so that your child focuses beyond the vaccination (e.g., “We’re going out for ice cream afterward”).

Remind older children that vaccines are part of maintaining a healthy lifestyle, just like using a car seat and seat belts for safety.

When it’s time to get the shot, the most important thing you can do is remain calm. Your child knows right away when you’re feeling anxious, and she will feel more anxious as a result.

Your child’s position during the shot can make a difference. Try holding your child in a way that’s more like being hugged and less like being restrained. Letting an older child remain upright establishes a sense of control and decreases fear.

Skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding, or pacifiers may soothe your baby during a shot. Drinking sugar water before or during the shots can provide some relief from pain, perhaps by replacing the plain with a pleasurable sensation.

With older children, try taking deep breaths. The child can leave loose the arm receiving the shot, take in a deep breath before the shot, and then release a full, relaxing breath out during the shot. Focusing on one’s breath provides a distraction that may compete with the pain.

Talk to your medical provider about using a numbing agent before the shot, like 4% lidocaine cream (available over-the-counter at most pharmacies). It is applied to the skin and numbs the area so that the shot is less painful.

Ask your medical provider about a shot blocker, which is a plastic tool that blocks the pain from the needle’s insertion. If your provider doesn’t have one, you can buy it online or at most pharmacies.

After the shots:

(Adapted from the Immunization Action Coalition, “After the Shots . . . ”)

Immediately after the shot, try to distract your child with a game, a cartoon, a stuffed animal, or a song. Don’t dwell on the shot once it’s over. Emphasize what went well and then move on.

If your child is fussy after vaccination or develops a fever, you can give acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil) to reduce discomfort. If your child is uncomfortable for more than 24 hours, or the fever reaches a temperature that your medical provider has told you to be concerned about, call your provider.

If your child’s arm or leg is swollen, hot, or red, apply a clean, cool, wet washcloth over the sore for comfort. If the redness or tenderness increases after 24 hours, call your medical provider.

Additional Resources

For additional information about children’s vaccines, check out the rest of Boost Oregon’s website, contact us at info@boostoregon.org, join our Facebook page, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Other national and Oregon-based resources include the following:

Conclusion

Thank you for taking the time to learn more about vaccines. We hope that you found this guide useful. If you have additional questions, please attend one of our workshops (visit events for dates, times, and locations), check out the resources listed above, and speak to your medical provider. All parents want to make the best decisions for their children’s health, and together we can ensure that every child gets the best shot at a healthy life.